Losing sight of a childhood dream

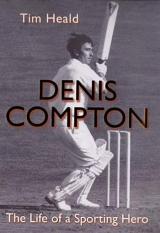

Simon Lister reviews Denis Compton by Tim Heald

Simon Lister

27-Jul-2006

|

|

|

The answer is that he was my father's hero, and hero to a million other schoolboys born just before or during the Second World War. Say `3816' to any of them now and they will tell you the number refers to the record total of first-class runs Compton scored in that glorious summer of 1947. How many of these men, I wonder, use `3816' as the pin code on their bank cards?

Compton was worshipped almost wherever he went. Even in the years before he died he caused grown men to be weak and silly. The actor Sir Anthony Hopkins

once introduced himself to the old cricketer at the Garrick Club with the words "I think you've given me more pleasure than any man alive". Why did Denis Compton inspire such devotion? Well, for starters he played cricket brilliantly for Middlesex and England. He was a full-of tricks winger for Arsenal. He was handsome and gave the impression of being the gayest of entertainers in a grey world.

This is Tim Heald's second bash at Compton. The original biography, published in 1994, has been tinkered with and material has been added. The most useful

information is the account of Compton's death and the reaction to it by his friends and family. Other additions, such as what Compton might have thought of Andrew Flintoff or the 2005 Ashes series, are too speculative to be of much use.

For the generation that - like the boy in the bookshop - knew nothing of Compton but would like to, this biography will be useful. It is thoroughly researched and contains many pleasant anecdotes. Plenty of room is given to Compton's early years and the experiences that shape a man; his time spent as a

teenager sweeping the terraces at Highbury and helping roll the square at Lord's.

Much less satisfactory is the author's explanation for Compton's defence of apartheid in South Africa, a defence which seems to be based on little more than not wanting to offend the friends he made while playing cricket there. Perhaps Heald became too fond of his subject to recognise fully Compton's ignorance and lack of inquiry when confronted with the reality of egregious state racism.

There is not enough sparkle in this account of one of England's most effervescent cricketers. A book about Denis Compton should fizz and pop like one of his chinamen on an uncovered wicket. It should tingle with the same excitement that Compton's batting brought to a generation battered by the war. It should be a rollicking reward for those who invested so much daydream time in the Brylcreem Boy.